|

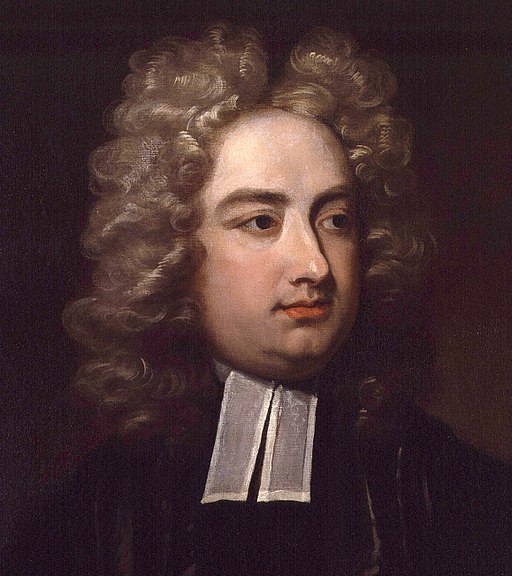

| Jonathan Swift (1667-1745) from a painting by Charles Jervas (c.1675-1739) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons |

Yet, the similarities that one can't help but notice also betray the contrasts that come to the surface as one digs deeper. For, while both men were deeply involved in the politics and public life of the time, it was usually from opposing platforms that they enunciated their views, often having the effect of engulfing them in controversy of one sort or another.

Indeed Swift was among those who spoke against Toland in the outcry that ensued from the publication of his seminal work, Christianity not Mysterious, in 1695. He was also among those who called into question Toland's parentage, describing him as a "priest and the son of a priest" in a 'Letter to a Member of the House of Commons of Ireland etc. written on September 3rd 1697' (cited in John Toland: Ireland's Forgotten Philosopher, Scholar ... and Heretic by J.N. Duggan)

The price that both men paid included exile although, in opposite directions for, while Toland found himself banished from Ireland, Swift probably felt that he was being banished to the country of his birth, upon finding himself on the wrong side of the fence, politically, in England.

Toland arrived in Dublin sometime prior to the publication of Christianity not Mysterious, after many years studying abroad in Scotland, England, the Netherlands. It is believed that he had hopes of securing a position of some kind in Dublin but, following the furore, it was not even safe for him to remain in Ireland. Thereafter, he spent much of the rest of his life in England (although he was an regular visitor to the Continent), championing and polemicising on behalf of various Whig causes. This, after all, was the political movement of the day to which he had always been closest.

Swift, on the other hand, started out, politically, as a Whig but, eventually crossed over to the Tories. Hence, while Toland largely welcomed the period of Whig supremacy that followed the ascension of Elector George Louis of Hanover to the British throne (as King George I), for Swift, this was the kiss of death in terms of his own political ambitions.

"When he sought a church appointment in England, in reward for his services, the best position his friends could secure for him was that of Dean of St. Patrick's Cathedral in Dublin. It seems that Queen Anne had taken a particular dislike to Swift and, made it clear that he would not have received even that position if she could have prevented it. Among other things, she regarded his work, A Tale of a Tub, to be blasphemous. With the return of the Whigs to power in 1715, Swift left England and returned to Ireland, it is said, "in disappointment, a virtual exile [and] to live like a rat in a hole." – see Writing & Literary on the 350th Anniversary of the Birth of Jonathan Swift (1667-1745)

Jonathan Swift, essayist, poet, political pamphleteer and contemporary of John Toland, died on this day in 1745.